Beyond Tribalism

“Tribalism is holding us back, and it’s time to move forward.”

The internet is surely one of the greatest inventions ever created, and one of the most dangerous. It brings us together by highlighting what we have in common, yet it also drives us apart by exacerbating our differences. The online community is a paradox in which the world is at once getting smaller and larger. We feel close to faraway people with whom we share mutual interests, but we feel further than ever from those with whom we disagree — even if they live in our own neighborhood. The ability to commune with like-minded people across the globe empowers us, but when we get lost in the affirming bubbles we create for ourselves, we forget how to get along with different types of people. In other words, online tribalism has made it difficult to find community in real life.

Even as I type this, I hesitate. I generally avoid the word “tribe” to describe my community. It can be a loaded word, one that too often was used by colonialists and white anthropologists to describe what they perceived as inferior cultures. I am keenly aware of this because my online community encourages open discourse about the lasting effects of colonialism, and people there have taken the time to engage with me on the topic. It seems to imply a simpler or more primitive social structure, as opposed to words like “society,” “culture,” or “community.” Additionally, for Native American cultures, it has a very specific meaning that has nothing to do with the way it is often used colloquially. Tribalism, on the other hand, has a very specific meaning in a contemporary context, and I am having a hard time finding an appropriate synonym.

Historian Yuval Noah Harari, in his book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (2011), traces tribalism to our ancestral past, a behavior pattern built into our very DNA that impels us to identify with the values of our own particular community. It makes us feel not only connected, but proud and loyal, and we defend or attack as deemed necessary for the protection or benefit of the group. This mentality has been deeply conditioned into humans by evolution, allowing us to survive and thrive in the world. Villages, towns, cities, and countries have sprung from our impulse to separate ourselves from others, uniting us in large groups under an implied agreement that anyone who lives in this village, town, city, or country are our people. Yet, while people within those larger communities may share a nationality and a cultural tradition, they still find ways to divide themselves: by race, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, status, and religion.

The internet is a place without geography. We form communities there that are divorced from the need for physical proximity, which is incredible when you think of it. For better or worse, they are also places where there is no longer a need to compromise or get along with people who are different from you. In the real world, it’s still necessary to get along with your neighbors. You don’t need to be best friends or share interests, but you do need to get along — you never know when you’ll need to ask them to turn down the music, or to count on them to catch your dog after it’s bolted. Historically, relationships with neighbors were a matter of survival. Extreme weather, thieves, invading armies, or protecting the harvest and water supply all required cooperation with the people immediately around you. On the other hand, there are no consequences if you don’t get along with someone online. You can simply choose not to associate with them.

As a writer for LGBT publications, I have personal experience with running afoul of online tribalism. Recently, I shared my article What about Whitey? on social media. In it, I argued that attacking white people is not a good strategy for achieving racial equality. Reactions were mixed, but the negative responses tended to accuse me of betraying my queer community. Amusingly, some readers even assumed that I must be white myself — otherwise, how could I possibly “defend” white people? One commenter ordered me to “sit down and shut up so that queer people of color can be heard.” They obviously overlooked the fact that I’m bisexual and Latino because that didn’t fit the narratives by which they understand the world. Some people are so committed to maintaining an antagonistic us/them online culture war that they will interpret any attempt at building peace and cooperation as a betrayal of “their” tribe.

Sadly, the people who directed those discouraging comments at me on social media want us all to fail at resolving the tribal conflicts splitting our society. I don’t imagine them to be bad people, but they’re certainly giving in to hostility stirred up by provocateurs with ulterior motives. The algorithms that control social media platforms are designed to amplify outrage because that increases engagement, increases the time we spend on them, and keeps us coming back. Similarly, online journalism is ever-hungry for our clicks and our attention, and so produces a seemingly endless stream of clickbait stories that reinforce our prejudices against one another. On top of that, authoritarian governments like Russia and China produce propaganda aimed at dividing liberal societies from within, in order to undermine our democracies.

We’re falling into their trap by choosing outrage over understanding. Rather than engage in a conversation and ask questions, we react with anger. If we are to mobilize against the specter of tribalism, it’s necessary to keep in mind that the people who benefit from these culture wars are motivated by self-interest and seek to gain money, power, and influence, often with blatant disregard for the consequences of their methods. Extremists on both sides benefit from erasing the reasonable center. They stoke the flames of conflict, emboldening prejudiced thinking and behavior — including the demonization of straight white men (I’m speaking to you, fellow LGBT activists). The people trying to keep these identity-based culture wars alive are imposing harmful us/them thinking upon the entirety of our society. If they can persuade us that the only alternative to one extreme (misogyny/homophobia) is another extreme (misandry/heterophobia), then those of us who advocate genuine equality are drowned out by the angry shouting.

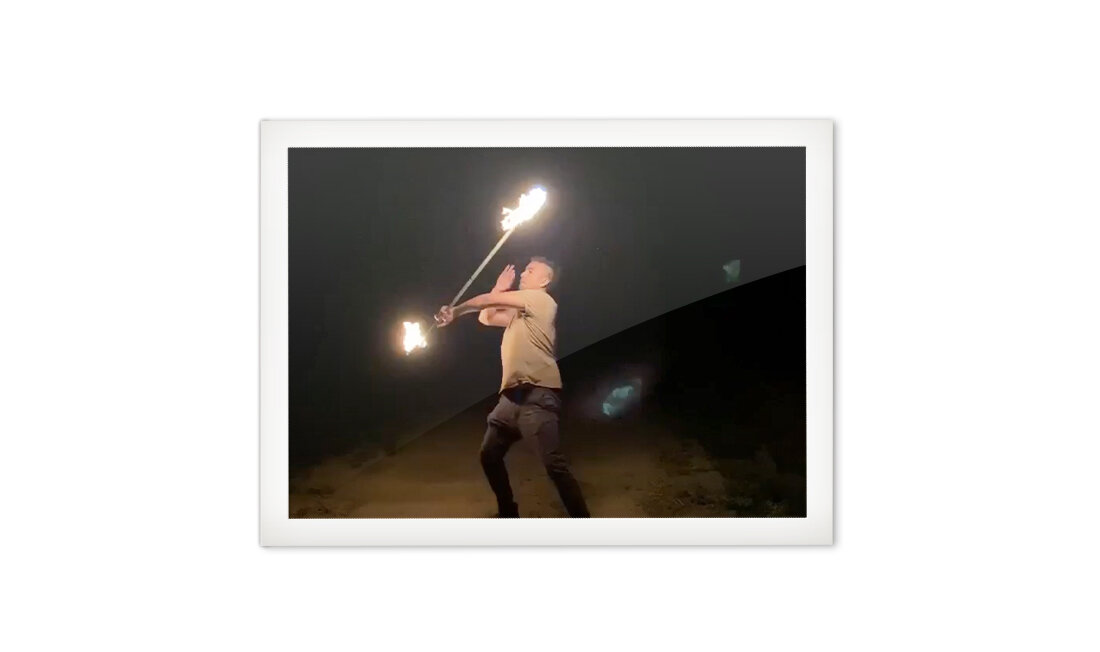

When I get offline, I am reminded over and over again how much I have in common with people who, at first, seem nothing like me. One of my hobbies is fire performance, a style of Flow Art that consists of the kinetic movement of objects (like a staff or a sword, darts, fans, hula hoops, etc.) in different patterns while they are on fire. It’s an exhilarating hobby, and beautiful to watch — especially at night. As it happens, the flow arts community tends to be pretty darn white. Since fire dancing is a major passion of mine, I spend a lot of time in the company of white people (and even — gasp — straight cis white men!).

Like many other fire performers, I try to go every year to Black Rock City: the 80,000-participant provisional city in Nevada, also known as Burning Man. It’s a massive event, with a huge program of camps and activities that offers something for just about anyone.

One year, I connected with a group called Polyglamorous. Their name is a play on the word “polyamorous”; they offered meetings to discuss ethical non-monogamy. The group sat in a circle and exchanged stories over cups of lemonade spiked with vodka. We talked about sex, relationships, jealousy, how many partners we had, and more. Most of the attendees were women, mainly straight, and — yep — white. Nevertheless, as a brown bi guy, I fit right in. I felt like I belonged — like I was part of the community. Confronted by people different from me in person, we were encouraged to find our commonality, rather than simply move on.

Tribalism may be hardwired into our DNA, but life offers us ways to overcome our baser instincts. Learning to live cooperatively in a diverse society is a matter of focusing on what we have in common — rather than on our differences. Fortunately, human civilization has made a lot of progress on this front. As evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker chronicles in his book The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011), warfare has sharply decreased over the last 200 years, and statistics prove that we are living at the most peaceful time in human history. This leaves me wondering: if we can overcome our tendency toward actual war, can we not also choose to avoid the “culture wars''? That’s what I had in mind when I wrote What About Whitey.

The impulse to find like-minded people and form communities is natural, but when this is filtered through the instinct of tribalism, it can devolve into divisive identity politics. It’s all too human to assume, rightly or not, that the expansion of one group’s rights (women, people of color, LGBT folks) must necessarily mean the erosion of another group’s rights (men, white people, cis straight folks). In recent decades, there has been some effort by cultural institutions to compensate for this effect, but too often, these attempts at social engineering have been worse than ineffective. For example: a careful meta-analysis of ”diversity training” seminars at universities and corporations reveals that they not only fail at their task, they tend to make members of minority groups less happy while simultaneously alienating members of majority groups. They achieve the opposite of their stated purpose: they actually increase intergroup hostilities. In other words, dividing people up based on race, sex, religion, etc., increases tribalism.

According to sociologist Musa Al-Gharbi, organizations continue to push this model of training not because it works, but because it gives them an opportunity to sidestep the issue, and an easy approach that allows them to say they’ve taken measures and done their best by assigning the work to “experts.” Such an approach serves as performative proof that they are on the “right side” of these social issues. But ultimately, these expensive trainings are about saving face — and protecting themselves from legal liability.

We cannot rely upon our institutions to resolve these problems for us, although they can be part of the solution. If we are to move beyond our tribalism, the responsibility ultimately falls on each of us to adapt for ourselves. We are faced with the advent of a new technology that has irrevocably altered the way we communicate as a society, but history shows us more than capable of rising to the challenge. We’ve learned to live with disruptive changes in communication before, such as the printing press, the telegraph, telephones, and the early internet. We can do so again. Online life presents challenges, but it also offers great promise if we can find a new equilibrium. When we learn to balance the benefits of our online and offline communities, we’ll have the best of both worlds. Just because we share certain qualities or interests with people on the other side of the globe doesn’t mean we don’t also have things in common with the people who live next door. Striking this balance is a matter of allowing our common humanity to overcome our superficial differences.

Published Mar 18, 2021

Updated Feb 21, 2024

Published in Issue IX: Community