Man Up and Take It: Do We Under-detect Men’s Suffering?

When we think about the relative success of men and women in our society, our minds tend to jump to examples in which men excel. We have only to look at the greater proportion of male CEOs, professors, scientists, and world leaders to come to the conclusion that being a man in our society gives a person an advantage. At the same time, patterns that run in the opposite direction — where men experience negative outcomes — don’t seem to attract much attention. We focus on the success stories while essentially brushing aside statistics showing that a greater proportion of men are homeless, incarcerated, high school dropouts, or affected by substance use disorders. Why is it that when we consider examples of gender disparities, we seem to only consider areas where men achieve success? And why, when we look at distribution among the lowest social strata, those who experience the most hardship, do we struggle to acknowledge the fact that men are vastly over-represented there too.

I first was made aware of this double standard in a masculinity seminar offered by my advisor, Dr. Roy Baumeister, during my graduate training. I walked into his class with the assumption that women have generally faced more challenging societal obstacles, both throughout history and today. After all, for centuries, women were denied educational and occupational opportunities that men could take for granted. It was not until we discussed men’s forced conscription and experiences in warfare that I began to question my assumptions. When we reached the topic of early working conditions (before the advent of legal workplace protections), I began to consider how societal stereotypes of men as breadwinners placed pressure on men to sacrifice their bodies in order to provide for their families. As the examples kept coming, I started to wonder why it had taken me so long to really contemplate this perspective.

Years ago, I decided to get a PhD in social psychology because I was interested in why the human mind operates (and makes errors) in the ways it does. My research has largely focused on how the challenges faced by our ancestors still leave traces in modern brains. My hypotheses are often birthed when I become aware of biased thinking, either on my own part or from a loved one. This time, it was my own bias against noticing the suffering of men that inspired me to look deeper.

Through a series of studies, my colleagues and I set out to examine the psychological basis for this unexpected asymmetry, beginning with the seemingly logical hypothesis of gender bias in our moral typecasting. Moral typecasting theory contends that when individuals observe or evaluate a situation involving harm, they instinctively make a value judgment regarding the involved parties, perceiving one as malevolent, and the other as innocent. This cognitive expectation makes sense, given that many moral violations — a robbery or an assault, for instance — fit into a dualistic pattern. From this angle, it seemed to follow that we would more readily classify men as perpetrators and women as victims.

However, as Kurt Gray and his colleagues have demonstrated, the human brain treats these roles as inverses and mutually exclusive. In other words, the more we perceive someone as a perpetrator, the more challenging it becomes to simultaneously perceive that same person as a victim. Since our psychological systems are ill-equipped to process ambiguity, we instinctively assign blame on one side of the equation and place our sympathies on the other.

That observation alone, of course, doesn’t really explain why a gender bias might exist in our tendency to label individuals as perpetrators or victims. For that, we must look at gender stereotypes. Throughout history, men have typically been characterized by our culture as having a great deal of self-determination over their lives and viewed as forceful, dominant, aggressive, and assertive. Women, on the other hand, have traditionally been seen as passive, gentle, yielding, and warm. Considering the attributes associated with the perpetrator and victim roles, it’s not hard to recognize how these gender expectations create bias in the dynamic described above. The agency we ascribe to men seems to fit the agency inherent in the perpetrator (or harm-doer) role, while the passivity we ascribe to women is consistent with that of a suffering victim, even though feminists have rallied against these assumptions for over a century.

There are additional reasons for us to instinctively cast men in the role of perpetrator. Men are more likely to be physically violent than women, which is reflected in the disproportionate percentage of male perpetrators in statistics around homicide. Moreover, in a global context, boys and men are typically more physically active than girls and women, and more likely to venture farther from home. In addition, men’s bodies have higher proportions of lean muscle mass than women’s. Research has found that increased musculature evokes lower levels of pity from others; the comparatively formidable physicality of men may make it more challenging to view them as deserving of sympathy.

Likewise, there are numerous reasons why we more readily perceive women as victims. Through the lens of evolution, such a tendency can be associated with reproductive roles. Women set the upper limit on reproduction; all other factors being equal, a group of 10 women and 3 men can produce many more children than a group made up of the opposite gender ratio. With this in mind, it’s not unreasonable to assume that natural selection has favored psychological mechanisms that protect women from harm. If so, our modern minds may possess relics of these asymmetric impulses, attuning our thoughts and emotions to more readily insulate women, relative to men, against peril.

With an awareness of all these factors, my colleagues and I undertook an examination of our tendency toward gender bias in our moral typecasting. We conducted six studies among over 3,000 individuals from four countries. In one, participants were asked to read a vignette depicting harm in the workplace. For this experiment, we specified the gender of the inflictor but left the recipient’s gender ambiguous. Participants were then asked to “recall” the gender of the harmed individual. Supporting our predictions, we found they were overwhelmingly more likely to assume that the harmed individual was female, even though we never specified any gender. People instinctively assumed a female victim!

Within the scenarios, we also manipulated whether the two individuals were labeled as “perpetrator/victim” or the more neutral “Party A/B.” When presented with “perpetrator/victim” labels, participants were even more likely to assume the harmed individual (or victim) was female. This pattern supports the notion of a cognitive link between womanhood and victimhood; when influenced by a framework implying harm, using words such as victim or perpetrator, this link becomes even tighter.

We recognized the possibility that some of our vignettes might have evoked extraneous gender stereotypes, skewing the results to reflect an additional bias beyond the one triggered by the word choices we used. To address this limitation, we conducted an additional study, this time avoiding the use of human attributes in the material presented to subjects. Participants from two distinct cultures (Norwegian students and Chinese managers) each viewed a series of brief videos depicting the interaction of two animated triangles. In one video, the green triangle appeared to poke the orange triangle. In another video, the green triangle appeared to poke the orange triangle, but the orange triangle retaliated. Participants reported the degree to which they perceived each of the two triangles as a victim and as a perpetrator. Then, they were asked to classify the triangles as either male or female. Across the videos, the results were the same. The more a participant perceived one triangle as a victim, the more likely they were to classify that triangle as female. Likewise, the more they perceived a triangle as a perpetrator, the more likely they were to classify that triangle as male. This pattern emerged in both samples, suggesting it was not a product of one particular culture. We appeared to be on to something.

Across all six of our studies, we consistently observed a pattern in which participants more readily linked women with victimhood and men with harm perpetration. Our results repeatedly supported the existence of a gender bias in moral typecasting.

Although I found this tendency fascinating, it was the consequences of this bias that really moved me.

While I was working on these studies, I saw evidence of this bias firsthand. After returning from a work trip to China, my father suddenly and unexpectedly developed bipolar disorder. His mania was so severe that he squandered his life’s earnings, left my mother, and got himself into countless altercations. He was arrested numerous times and banned from local establishments. Shop owners, police, and community members saw him as a monster, not as a victim of mental illness. Even though he had always been a tender-hearted introvert, his newly erratic behavior had turned him into a menace to be feared. He spent a year in and out of homeless shelters, jails, and mental hospitals.

If women are more readily typecast as victims, logically, this should amplify the extent to which we experience pity and moral outrage in response to their suffering. Indeed, this is exactly what our studies revealed. Consistently, participants felt more pity and outrage when women were harmed in comparison to examples in which men experienced identical harm. This bias emerged even in the context of job loss. Other research reveals that when men lose their jobs, they experience worse outcomes than women who similarly become unemployed. Men’s greater suffering makes sense in this context, given our stereotyping of males as “the breadwinners.” Nonetheless, participants in our studies felt greater moral outrage and pity when it was a woman who had been laid off than they did when it was a man. These findings suggest that, even in cases where we should presumably be more capable of perceiving men as victims, our emotions continue to respond as though women have experienced greater suffering.

Another of our studies uncovered some of the consequences of typecasting men as perpetrators. We presented two workplace harassment scenarios in which an individual makes an ambiguous and potentially objectionable comment to a co-worker, manipulating whether the comment was delivered by a man or by a woman. When it was ostensibly made by a man, participants desired stronger punishments and were less likely to forgive him or support his workplace advancement, compared to when a woman made an identical comment. These patterns suggest that when men are presumed to have inflicted harm, we will feel less inclined to give them the benefit of the doubt. Indeed, data from real world court rulings cohere with our findings. Male defendants are more likely to be found guilty and receive longer sentences than female defendants, even after holding the severity of the crime constant.

Taken together, our studies strongly support the hypothesis that people’s moral judgments are consistently swayed by gender. Because men more closely fit our assumptions about perpetrators, we more readily believe they intentionally inflict harm and respond with castigation and scorn. Because women more closely fit the prototype of victims, we more easily see them as suffering, and consequently experience pity and an urgent desire to help them. Since our tendency to morally typecast makes it challenging to see individuals as both perpetrators and victims, we instinctively look for someone to blame and someone to rescue, without recognizing the nuance inherent in social interactions.

Our findings also suggest we rely on gender stereotypes as we assign these roles. When faced with men’s suffering, it is easier to view them as responsible for their own suffering because we see them as independent and in control of their lives. We can’t help but attribute agency to them, so we blame them for their misfortunes. Indeed, participants in our samples donated less money to homeless shelters serving men than those serving women. It’s this bias that affects men like my father, whose suffering from severe mental illness goes largely unseen but who are readily cast as perpetrators of harm. These presumptions felt palpably unfair as I watched him drift from shelter to shelter, desperate for him to get the services he needed. With a homeless population that is predominantly male, it seems obvious that many other fathers, brothers, and sons face similar struggles.

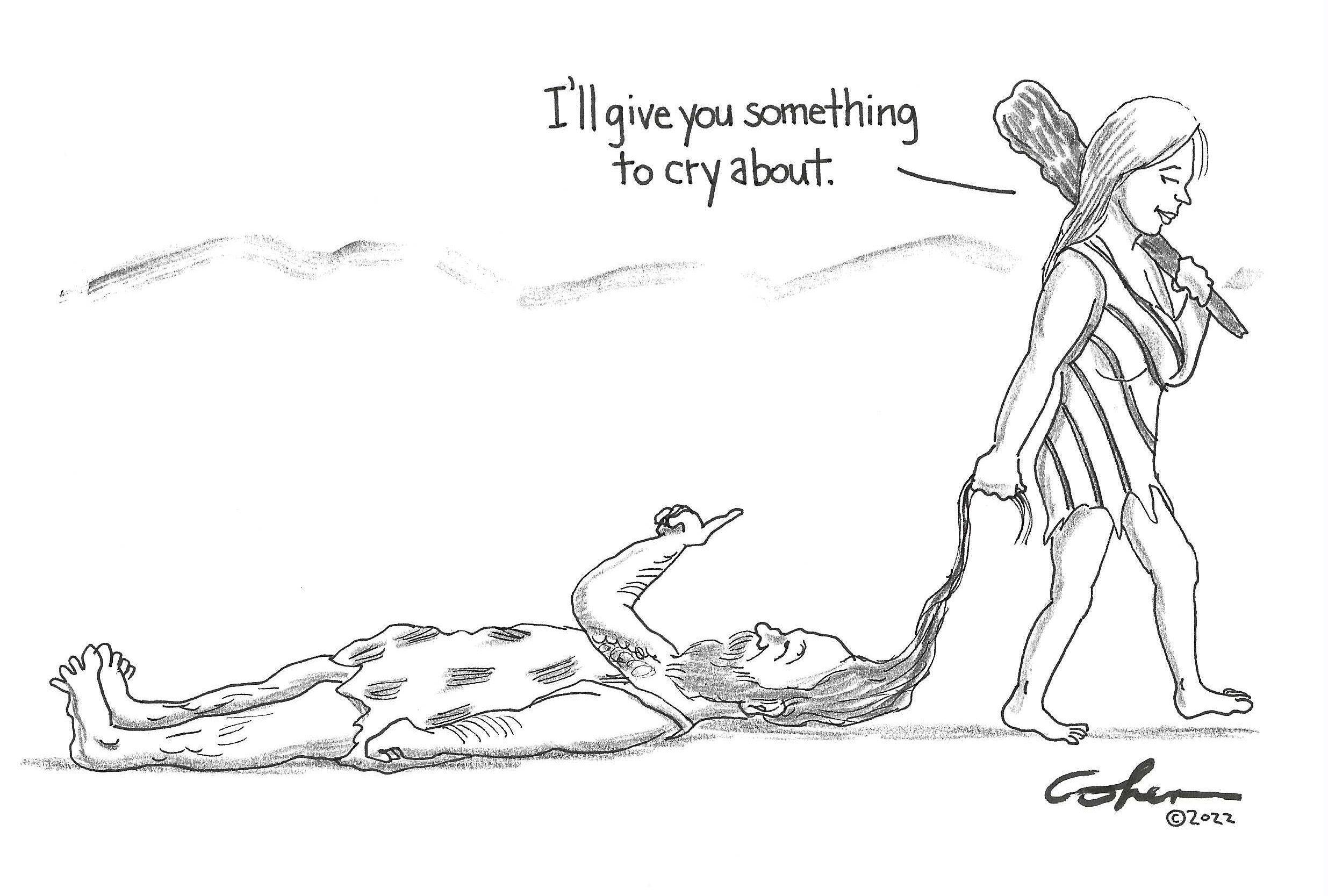

If we take a hard look at our community, we find many examples of men’s prodigious suffering, including homelessness, substance abuse, school dropouts, and suicide. Yet, these examples are generally overlooked when we think of gender disparities in suffering. Because of our expectations about men, it is cognitively more challenging to recognize their suffering and respond compassionately. The stereotypes that lead us to more readily assume men are capable leaders are the same ones that cause us to feel less empathy for their suffering. The real-world impact of this tendency is unmistakable. While greater assumptions of agency may be advantageous in boardrooms or the voting booth, they are costly for estimations of moral worth. We relegate men without question to community roles that require physical suffering and sacrifice, but when they suffer, we feel comparatively little compassion. When it comes to deciding who deserves our sympathy or our aid, our cognitive biases lead us to presume that men should just man up and take it.

Published Mar 18, 2021

Updated Feb 21, 2024

Published in Issue IX: Community